|

|

modern design roots

use materials honestly – display linkages openly

Most have heard the term minimalist design, but few recognize its connection to the roots of modern design. These roots refer to a German school founded in the early 1900s by Walter Gropius called the Bauhaus. However, its true lineage spans much of history. For example, ancient Japanese architecture’s spartan use of materials, interlocking wood joints, and paper walls are minimalist. Alternatively, Scandinavian furniture was also minimalist before the trend became fashionable. Minimalist design sprung from many roots. Each had its own social or industrial forces affecting the design outcome. Modern architecture and industrial design started from this deep lineage but with a new twist. Minimalist designs reflect a deep connection between how material form follows function.

|

|

|

modern

design was off to an honest start

Architectural and product designs influenced this movement from around the world. The significant Bauhaus breakthrough was treating modern materials and fabrication techniques honestly. Instead of hiding joints, for example, the Bauhaus Barcelona chair celebrates the potential of high tensile strength steel as an open and graceful cradle for the soft, subtle pig skin-covered cushions. Each component’s legs and cushions float independently yet integrate beautifully and seamlessly.

|

Many recognize the Barcelona chair, but few know how radical of a design it was when it was shown as part of the German Pavilion at the International Exposition of 1929. |

|

tree

offshoots and branches

The roots of modern design can be attributed to the Bauhaus School of Design. But another outgrowth of this movement sprung from an industrial base. That outgrowth is called reductionist. By the early 1900s, the industrial revolution had been underway for around 200 years. During this time, arguments for theories and principles of science had been going on in the Royal Society for 300 hundred years. Every field of science was exploding. Giant leaps in Chemistry, physics, astronomy, aerodynamics, and biology were being made. D’Arcy Wentworth Thompson’s “Growth and Form” postulated how forces and functions shape natural organisms. This concept and ideas from psychology and sociology became part of our lexicon. One might say the logos of human endeavor were firing on all 24 pistons—a perfect seq-way to the Macchi M.C.72 Seaplane below.

|

minimalist

design by choice or necessity

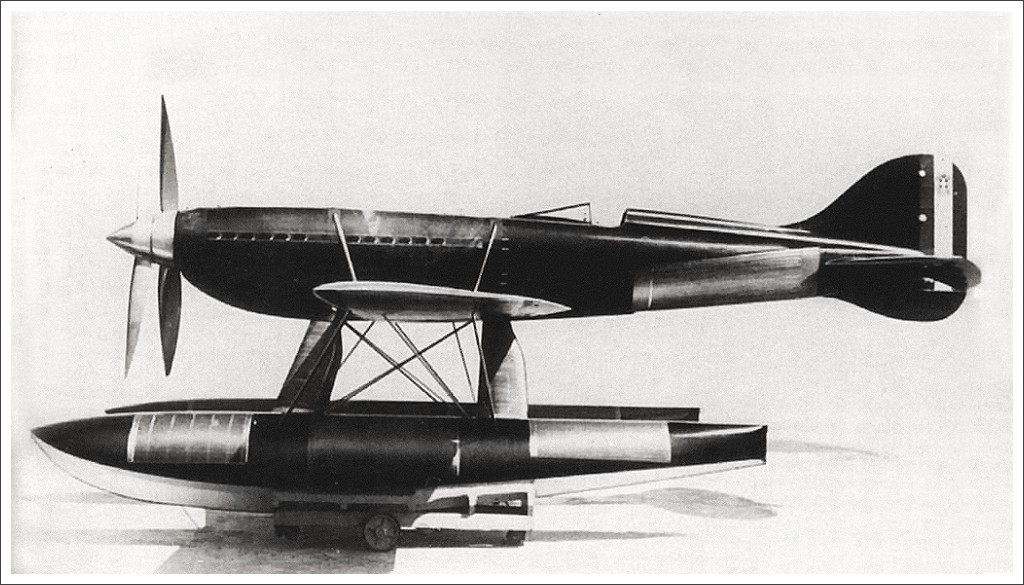

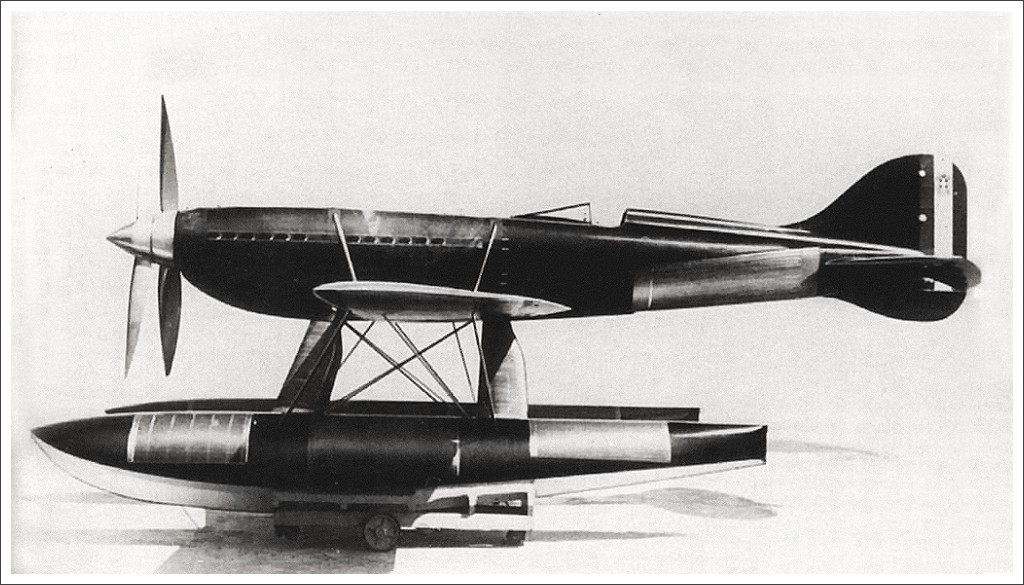

Some minimal design is done by choice, while aircraft, for example, are minimal because designing lightweight, high strength, and low drag structures leaves no room for superficiality. The Italian Seaplane Races in the 1930s, just before WWII, is a perfect example of how competition and the pursuit of speed can result in beautiful forms following function and minimalist design by necessity. Behold the Macchi M.C.72 Seaplane, considered one of the most beautiful craft ever designed by many.

|

|

minimalism

not always pretty

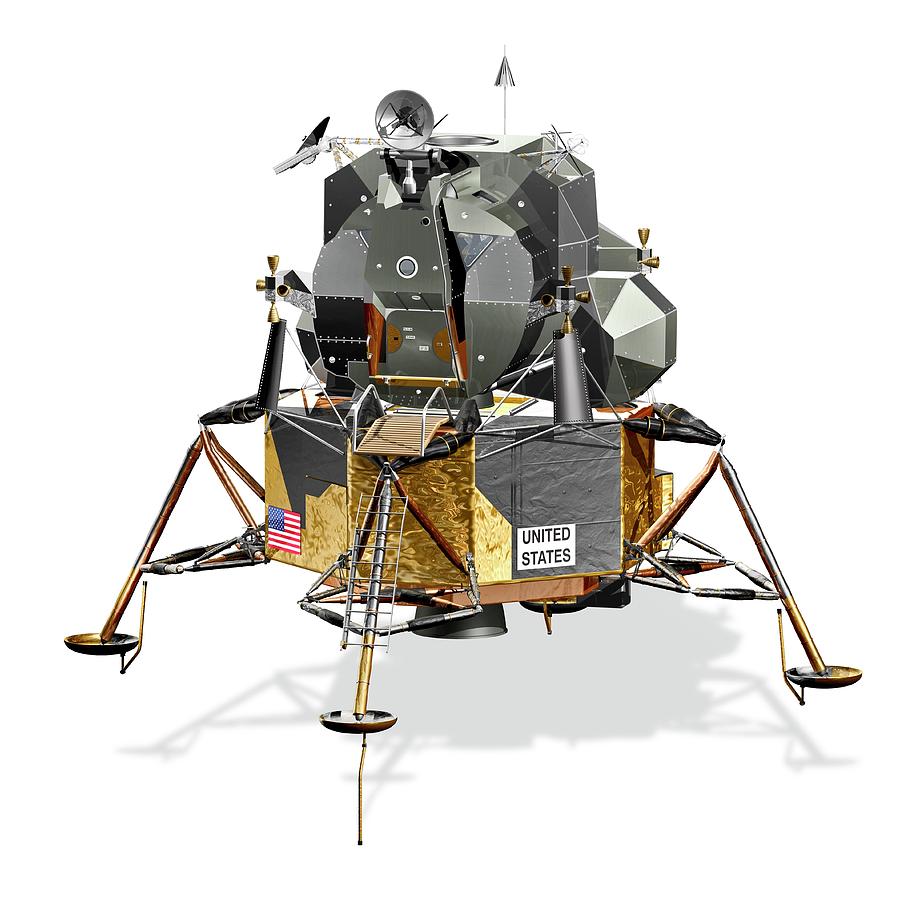

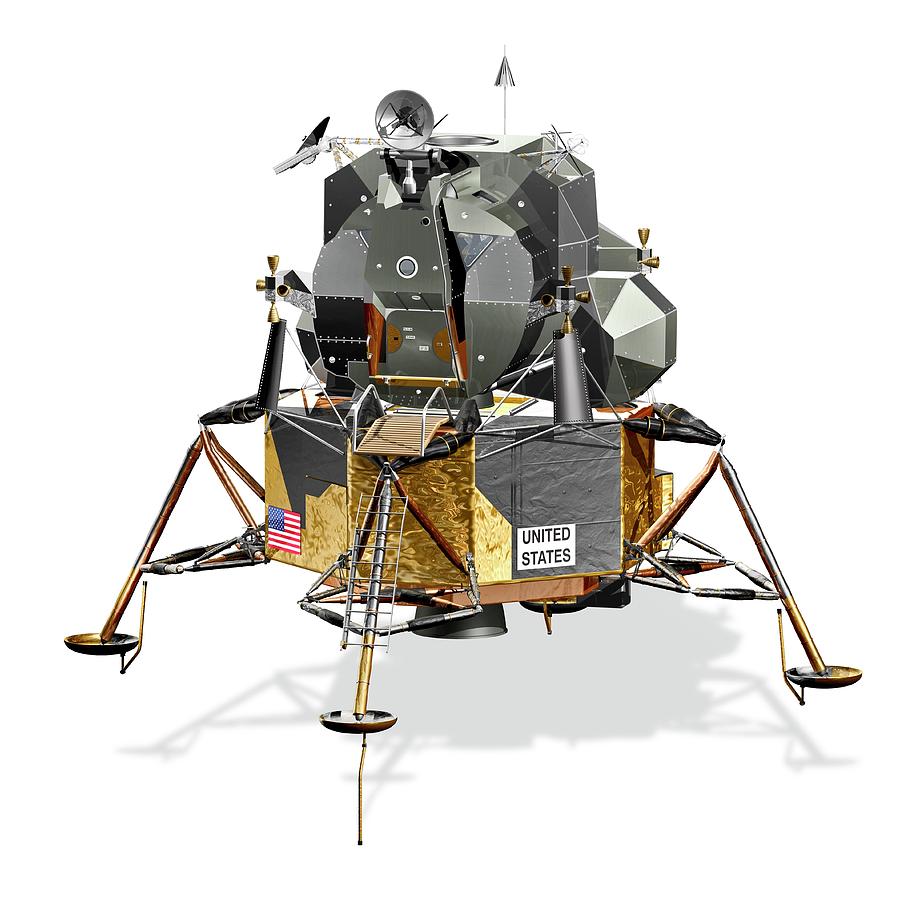

Not all minimalist designs tug at the romantic heartstrings in the same way. The Lunar Lander is an example of form following function and minimalist design. So much so that the landing struts are so light they cannot support the Lander in Earth’s gravity. Though some find this purity of form engineered without the constraints of an atmosphere ugly, others see the beauty of human creation.

|

nature

we have much to learn

In a way, the lander represents the principles of D’Arcy Thompson’s “Growth and Form.” It is almost organic in the same sense that the scanning electron microscope revealed this elegant virus years later. Today, scientists are engineering Nanobots. Someday, these molecule scale machines may be inside you, proving that minimal design is more than skin deep.

|

|

It is hard to beat nature when it comes to minimalist design. See any unnecessary parts or wasted materials on this virus?

|

|

|

bergstrÖm to morse

the unnoticed minimalist design

Though the beauty and elegance of minimal design are often easily seen, sometimes they hide in plain sight or are buried internally. Knut Edwin Bergström patented the modern worm-drive hose clamp in 1896. Since then, the lowly hose clamp has found its way into countless products, from automotive to the most advanced rocket engines. The point is that this marvel of clamping engineering is taken for granted, and frankly, it shouldn’t be.

|

|

Another example of minimal design hidden from the eye is the Morse tapper. It was developed in the 1860s by Stephen A. Morse of New Bedford, Massachusetts. The Morse taper-shank is commonly used in tailstocks of lathes and other precision machine tools. This elegant and simple cone-shaped locking linkage works only if the mating surfaces of each component are held to very tight tolerances, which is why it is not used in consumer products… oh wait, Saeng fairings used Morse tapers in its mounting system. Also worth noting is the aerodynamic purity of the saeng fairing’s body. Its beautiful minimalist form follows its function of stretching an air capsule around its rider and proving that minimalist design can run throughout the product. For more on aerodynamics, see The Holy Grail of Air Management.

|

|

Note the minimalist form follows the functional design of Saeng’s Quantum fairing. Many aircraft, by necessity, follow these design fundamentals. Saeng followed these principles by choice, not market necessity.

|

closing

a final thought

This brief tribute to modern design is intended to add perspective and give a sense of how much we owe to those who went before us. I welcome comments, corrections, or recommendations.

Safe passage,

Chuck Saunders